We are in a time of breakdowns and breakthroughs. The experience of the global covid19 pandemic has cast a bright light on the frailty in our global economies, has highlighted our inability to adjust to complexity, uncertainty and volatility, and accelerated the conversation about what needs to change in our world. Not just to adjust to the possibility of future viral anomalies, but to the greater challenges following in its wake.

Climate change. Biodiversity loss. Soil degradation. Ocean acidification. Economic and social collapse.

We know that these challenges are driving deep systemic change. It’s no longer a question of why we have to change, but how. This series focuses on a key aspect of how we design regenerative economies to address the imbalances in our current thinking — the economy and power of place.

The happiness of your life depends on the quality of your thoughts. Marcus Aurelius.

The world we have created is a product of our thinking; it cannot be changed without changing our thinking.

Albert Einstein

You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the old one obsolete.

Buckminster Fuller

Three quotes from three huge thinkers. All of which point us towards where transformative change really happens. So far in this series we’ve examined some of the challenges with our existing global economy. We’ve looked at the trajectories of different scenarios for the future of humanity and the existential threats we face. We’ve explored why reinhabiting and reconnecting to place might be helpful. Now we are looking at where transformative change really begins.

Cast your mind back if you can to the time of humans as hunter-gatherers. Early hominins ate berries, plants, rabbits, mammoths, their nomadic paths following the growth of seasonal vegetation and animals to hunt. Although they had extensive knowledge of plants, it wasn’t until around 10,000 years ago that simultaneously in the Euphrates/Tigris, India and China, developing minds looked at a grass with clusters of seeds at the top and began to wonder what it would be like to grow more of them in one place. Those same minds must also have worked out that if you crushed the seeds a white powder would emerge. And if you mixed it with water and built ovens in which to put it, you could create bread. All without ever having seen a You Tube video, a loaf of sliced bread or eating a Big Mac bun! Human minds were ready for a developmental and imaginal leap forwards into the agricultural era.

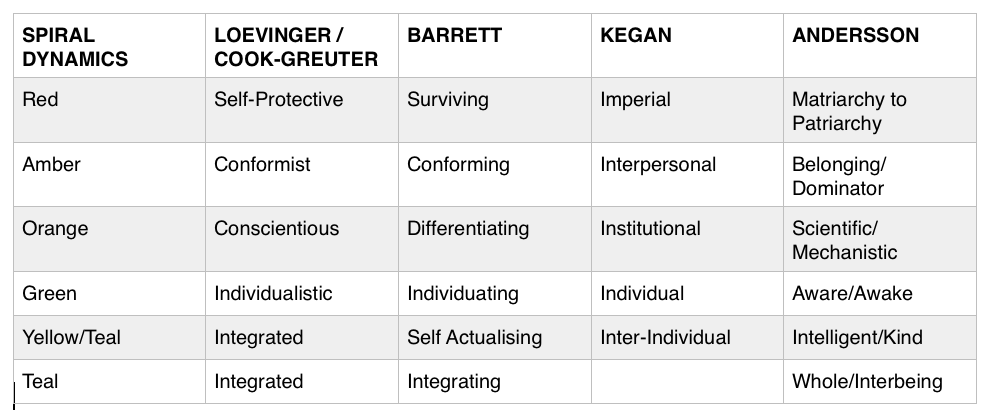

Regenerative study encompasses many fields; archaeology, sociology, anthropology, biology, ecology and developmental psychology among them. It is the convergence of some of those fields that is enabling a new leap forward in human thinking. The rapid advances of the latter part of the 20th century and the early part of this one in all fields of psychology has meant we have a far greater understanding of how human beings develop through different stages of maturation than we did when Maslow first produced his hierarchy of needs. From Jung and Maslow; Rousseau and Watson, Ryff to Seligman, Loevinger to Cook-Greuter, Kegan, Piaget, to Clare Graves, Don Beck, Christopher Cowan and Richard Barrett — we now have a much clearer picture of the pathways humans take throughout their lives as they grow, develop and mature. We also have a far greater understanding how the way in which we think shapes the design of the world around us — economically, socially, politically, architecturally, organisationally.

Seminal works from thinkers and authors like Otto Scharmer of The Presencing Institute and Frederic Laloux author of Reinventing Organisations have made correlations between the dominant paradigm of thought and the accompanying organisational form. In doing so they observed how shifting our thinking is a foundational pillar of how we might transform our societies to overcome the existential challenges we have created for ourselves. Writers such as Charles Eisenstein have explored the convergence of quantum physics with spiritual belief. Leadership experts such as Giles Hutchins and Laura Storm have looked at how cultural change has shaped the way we lead.

This is vitally important for place-potentialists to understand. Wewill not change the way we design our places unless we can change our thinking. Many have shaped this narrative as zones of disconnection or the story of separation. Let’s explore a little more.

The Story of Separation

It’s generally agreed by most developmental psychologists that human beings advance their growth in sudden leaps and bounds. These leaps can be seen both as shifts in human society over long periods of time but also correlate to the potential for individual growth and change during a single lifetime. Different fields give different names to different levels but there are general similarities across all.

If we track modern human development over the last 10,000 years, we can see how different ways of thinking that arose over thousands of years, gave rise to the story of separation.

- Separation between nature and humankind, where we shift from being interconnected with and interdependent on nature, to a dominator role where nature is ours to plunder, control and manage.

- Separation between humans and other humans through constructs such as cities, walls, housing; but also nation states and a process of ‘othering’ that includes nationalism, racism, religion, sexism, colonialism.

- Separation between our masculine and feminine psychology where we began to value our masculine qualities over our feminine qualities, which helped to develop our right, rather than left brain characteristics.

- Separation between spirutalism and science, where we lost touch with our internal sense-making and intuitive connection to the living world, in favour of relating to the world through externalities -whether those were analytic data or the opinions of others.

Giles Hutchins and Laura Storm summarised this in very elegant graphics in their book Regenerative Leadership.

Spiritual historian Anne Baring speaks of the pre-agricultural period as the Lunar Era , the last period of time in human existence when we lived in harmony with nature and each other. A period led by wise shamans who advised the tribes, and one of reverence for life through the image of earth as a great womb, bearing renewing life.

Survival Consciousness: As the hunter-gatherer tribes first began to group together into larger communities and settle in specific places around 10–12,000 years ago, a new way of thinking about the world arose which we might think of as Survival . In order to manage the new complexity of inter-connected tribes, we first saw the emergence of chiefs who ruled through fear, oppression and hierarchy. They managed group integrity through top down authority and clear division of labour. The dominant lens through which people viewed the world was power and authority. Disputes about territory between tribes gradually began to be more commonplace.

A new image of leadership began to take hold that replaced the relationship with the earth mother; that of the heroic leader, a triumphant warrior leading and winning battles. At the same time new religions appeared. Instead of multiple gods of embodied in the elements of nature, monotheism appeared in the major religions that are still with us today; Judaism, Christianity, Muslim, Hindu and Buddhism. Although all of these religions had higher consciousness at their heart, many were ‘captured’ by the emerging patriarchy and hierarchy of the times and transformed into organisations designed for societal management, control and power.

Even at this early stage of our development, it’s clear through archaeology that from the earliest cities, we designed our built environment to reflect safety and security, hierarchy and power. The foundational model for cities such as Damascus, Jericho, Eridu, Uruk in Mesopotamia and Phoenicia and Summaria were large strong outer walls for protection of those within. Society divided roughly into three main classes; government officials, nobles and priests were at the top; second was a class comprised of merchants, artisans, craftsmen and farmers; on the bottom were the prisoners of war and slaves. Commoners were considered free citizens and were protected by the law.

Palaces and temples served as socio-economic institutions and in later times were used as storehouses, workshops and shrines. Everyone in Mesopotamia lived in a house; smaller ones for the poorer people and larger two-story houses for the wealthier. Houses were built from mud bricks, plaster and wood. The strong defensive walls provided protection and safety for the people within but began the process of separating humanity from nature which was largely outside the city walls, and the process of separating people as ‘own space’ and ‘privacy’ — a previously unknown concept — became a norm for the wealthier groups.

Conformist/Belonging Consciousness: first arose somewhere around 4000BC, probably in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, China’s Yellow River, Mesoamerica, the Andes Mountains in South America fairly concurrently as agrarian society developed and deepened. Agrarian societies tended to have deep caste systems and social structures, and had formalised religions and customs with a founding mythology of some kind. Belonging to a group that provides security and safety is hugely important, as the alternative is rejection, isolation from the safety of the tribal community and almost certain death.

Agriculture became the defining factor in re-shaping the landscape and architecture of the times. As more people who were not food-producers gathered in one place so agriculture had to become systemised to support such populations. Formalised agriculture produced irrigation systems, grain stores, windmills, and corn-grinding mills on adjacent rivers. Whilst defensive walls remained a dominant feature, other huge structures began to appear: pyramids, cathedrals, temples of worship. The replicable processes of the annual harvest, religious ceremonies and defined roles to structure society give this paradigm an affinity to safety, certainty and predictability that is reflected in the geometric precision that is beginning to emerge in design, whilst the power and prestige represented by size of structure is still relevant.

Structures arose to manage the needs of human inhabitants..While early cities were always built on rivers to provide fresh water supplies, as settlements grew up to support the transportation of goods and minerals between cities, so additional structures like aqueducts appeared. Early clay sewage systems have been found in Mesopotamia at the Temple of Bel at Nippur and at Eshnunna. Clay pipes were later used in the Hittite city of Hattusa.

This period in European history also heralded the a new level of power and control by wealthier elite parts of society. The enclosure of the commons, the ‘gift’ or capture of large tracts of fertile land by royalty and robber barons of the day has had massive ramifications for the experience of humans today, as it established the possibility of ownership of the life support systems on which we depend. It can also be seen as the practice ground on which to practice and learn about how to establish a process of colonialism.

During this period in Europe, there was a prolonged period of cold winters known as the little ice age, in which crops failed and widespread starvation spread throughout the continent. The dominant force in the geography — the Catholic Church — found itself under pressure to explain the suffering of peoples. It’s authority was threatened. In a move that would not seem unusual in today’s political propaganda powerplays, the Church issued the Maleus Malleficarum, a Papal Bull which would usher in a century of persecution of anyone associated with nature’s wisdom. Perhaps millions of wise village women and men died during this period. Nature — and her ‘associates’ — became the enemy. One of many vilified organisations in history was born as a result of this period — the Spanish Inquistion.

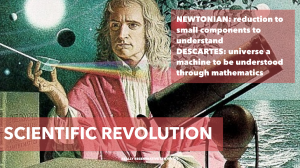

Scientific/Mechanistic Consciousness. As the sciences became established during the Renaissance period, the scientific mind became fascinated by understanding the mechanisms of life; anatomising living beings to understand their component parts and how each worked. The dominant paradigm of thought was of the world as a complex model of cogs and parts whose inner workings could be seen, understood, managed and controlled.

Scientists such as Newton discovered the ‘forces’ thatcontrolled the earth and our behaviour. Galileo radically changed the way we saw the place of earth in the Universe. Philosophers, rationalists and empiricists like Francis Bacon, Descartes, Spinoza and Leibnitz had a profound effect on the way in which people of the time shifted their thinking. Often referred to as the ‘father of the scientific method’ Francis Bacon’s writing and language underlined the idea that nature existed for human exploitation. Descartes gave us the idea of the universe as a machine, to be understood through precision mathematics.

Finally Darwin gave us a theory of evolution. The reductionist and mechanistic mindset which has arisen seized on a key statement as one which underscored how the worldview was developig. Survival of the Fittest. Whereas what Darwin really showed was that the most adaptable, the most agile creatures are those most likely to evolve and remain. Although competition features as one way of relationship in nature, there are many others such as mutualism, commensalism, predation and amensalism. Yet competition and even predation became benchmarks for human behaviour..

As the scientific era gave way to its inevitable output — the industrial era — it also brought with it aspiration and ambition, which, coupled with the idea that an individual could be anything they set out to become, gave rise to enormous leaps in quality of life for many human beings. The ability to imagine and experiment free of the constraints of a rule-based dogma, allowed humanity to move from a largely agrarian society to an industrialised fossil-fuel dependent machine in a period of 100 years.

The scientific/mechanistic mindset is the single most important and influential worldview to have contributed to the rise of our global extractive economy. From the scientific and industrial worldview, where you view all nature as functional parts to be understood and controlled, nature becomes ever more subject to the service of humanity. Nature’s precious resources became commodities along with the commodification of people. Her forests plundered for wood, her rainforests cleared for mono cropped agriculture, her rock industrially mined for metals and ores, her soil compacted and deadened through machinery and chemicals, her waters choked with pollutants and plastics, her animals bred and farmed to death. When all things are parts and not wholes, the systemic and interconnected view of the world is lost. When the interconnected view of the world is lost, unintended consequences that have ramifications across systems become the norm.

This worldview is readily evident in our organisations today where management theory is dominated by productivity, profitability, efficiency — all neatly categorised in disconnected silos. It’s present in the call centre cubicles, assembly lines, factories, intensive cattle feed lots, car parks, so-called ‘new towns’ and series ranks of little boxes housing estates of the late 20th century devoid of spaces in which humans and nature could come together.

It can also be observed in the places we have built in this expansive period, particularly in the United States. The medieval cities of Europe grew organically as more and more villages clustered together to form metropolis. London and Paris are good examples. They are untidy, disorganised and highly differentiated in their characteristics, compared to the modernity of grid-based, high rise grandeur of 1930s urban sprawl in the US — from New York’s organised skyscraper system to Los Angeles and San Fransisco’s wider-flatter grids.

It’s visible in the explosion of mass tourism where thousands of us cram in rows, seats and boxes, into aircraft, hotels and onto beaches at the cheapest possible rate, oblivious to the environmental and social impact that hundreds of thousands of migrating humans can cause to local nature and people. It’s demonstrable in the high-rise 70s developments in southern Spain in Europe, the opulence of destination Dubai, the colonisation of Caribbean islands by US private investors, royalty and celebrity, and generation Easyjet.

It’s there in the rank and file of endless mono crops in the vast wheat fields, palm oil and soya plantations, chicken sheds, pig stalls, and shining plastic roofs of Almeria in Spain. Constant growth, improved productivity, efficiency, profit, production at the lowest possible cost have been the winners. The environment, human quality of life and all future generations of living things have been the losers in this war of attrition.

Pluralist Green/Familial Consciousness: Scientific/mechanistic mindset might sound a total disaster, but of course that’s not true. It has pulled many people out of poverty, increased our standards of living, education, life expectancy — all good things most of us would say. But at a price that is shaping up to be an existential threat to our species. And yet all is not lost.

Sometime in the 18th century another worldview began to arise — almost in denial of the mechanistic nature of the scientific age. It first appeared in the anti-slavery abolitionist movement in Europe — a moral outrage against the treatment of so many African peoples enslaved to provide cheap labour for the growing commodity industries of Europe around the world. It took deeper root in the US abolitionist movement, the democracy struggles of the suffragettes, and really flowered in the social revolutions of the 1960s and the environment/NGO movement that grew out of that shift in the 80s and 90s.

In this consciousness, people are keenly aware of the social and environmental damage of the achievement era, and began to replace its exigencies with social and environmental justice. Sustainability was born here. Corporate Social Responsibility has its home here. It works from a perspective of developing positive values, empowering people within existing hierarchies to participate and question, and considers a much wider variety of stakeholders. It could be described as a ‘do good’ paradigm of thought or at the very least ‘do less harm’, ‘stop the rot’. It aims to protect and preserve what is left of our decimated nature, and to heal the hurt of our broken people.

The urban farming movement was born here. Community farms and gardens, eco-villages, farmers markets, the organic food movement and all its attendant small craft brands — all find their roots and began to flourish through this lens. The whole environment and conservation movement first appeared out of this consciousness. The idea of sustainable tourism rose from this shift away from performance-driven achievement, numerical, destructive destination plans. We saw the birth of eco-tourism, which has flourished in many small pockets of the world, most notably celebrated in Costa Rica, Ecuador, small game reserves in Africa, and in the management of national parks all over the world.

This worldview is having a significant impact on the places of the world already. Many are positive in that they are slowing the decline of species, improving habitats, protecting at risk wetlands but also improving living conditions for people alongside greater community participation and engagement in decision-making.

Alas, sustainability and corporate social responsibility, whilst a step in the right direction, are not sufficient to either halt economic, social and environmental collapse, or make a dent in the need to renew the potential of the human spirit and regenerate nature’s capitals to restore balance in our planetary ecosystem. Which is why we need a worldview shift that embraces a new paradigm — the living systems paradigm.

The Economy of Place is a series of articles by Jenny Andersson that are edited parts of her unpublished book Renewal. There are 20 parts to this paper which will be published here in due course. If you would like early notification of future releases, please register at Really Regenerative — Economy of Place.

Many people have helped me shape these narratives. I stand always on the shoulders of giants in regenerative economics and business like Carol Sanford and Kate Raworth, regenerative leaders who understand place such as Pamela Mang, Ben Haggard, Daniel Christian Wahl, but also many anthropologists, ecologists like Joanna Macy, developmental psychologists, bioregionalists, regenerative finance specialists and many others. I know so much less than they. If I ever publish the whole book I will reference you all but my gratitude is not less because I can’t mention you all here.

Recent Comments