I have always been a deep admirer of Donella Meadows. It is one of the few regrets in my life that I never got to meet her and experience her energy in person. When we speak about someone who is visionary, she is one of the first people I think of. Imagine being able to recognise and write about limits to growth more than 50 years ago!?! Even right in the face of the complex existential threats we face from exceeding planetary boundaries and pushing many of our life support systems towards collapse, we still fail to grasp the idea that constant economic growth is inconsistent with a finite planet.

Many regenerative designers and thinkers often refer to Donella’s equally interesting work on interventions in systems to create change. They are still regularly cited and used as a basis for systems change. Yet more evocative to my mind, more connective and emotive, were the 14 interventions for human behaviour that Donella called dancing with systems.

In the DESIRE lighthouse project we are grappling with the system we think of as the built environment, particularly urban spaces. How will we create inclusive urban spaces that respect the limited resources of our planet? How can we design irresistible approaches to circularity, and circular society? What does it even mean to try to think about that? So I’ve dug into Donella’s wisdom to see if I can imagine what her advice might have been to us. What questions might she pose to us about the systems we’re dancing with?

1.Get the beat.

“Before you disturb the system in any way, watch how it behaves”, Donella said. There’s a rhythm to life. A powerful beat. It’s different in every place in the world. Kalundborg is not Riga. Riga is not Cascina Falchera. Cascina Falchera is not Ljubljana. One of the most destructive things we do in our current culture, in our pursuit of scale and replicability in order to maximise efficiency and profit, is to treat everything generically. We treat agriculture systems and soils as if they were the same everywhere. We treat human communities and economic systems as if they were the same everywhere. Homogeneity kills the very creativity and diversity of culture upon which all living systems thrive.

We call the deep pulse of each place it’s Essence. Or Bio-cultural Uniqueness if you prefer. Both work. It is at the heart of what causes life to thrive in your place. It’s the way in which a place processes life, which is reflected in human culture and economy. Of course we humans think that we create human culture and economy.

But what if the very rocks, waters, flora and fauna have a role to play that we should try to hear? What different approaches to buildings might we take if we take into account that what Riga really wants to be is a sand-dune system? What are the qualities of a sand-dune ecosystem? What if just the simple act of trying to hear those beats, reconnects us humans to nature and other life on earth, and helps us to realise compassion and concern and we start to seek harmony and alignment with nature instead of control and utility?

If each place on the planet is healthy, with reciprocal relationships between human communities and natural ecosystems, not only can we gradually recreate a whole thriving planet, what you can also do is ensure the ongoing differentiation of culture.

How can we in DESIRE value, seek, analyse and report on the unique differences of place in our project rather than – or at least as well as – looking for common insight?

2. Listen to the wisdom of the system.

At Really Regenerative we listen to the wisdom of living systems. Living systems are self-organizing, nonlinear, feedback systems which are inherently unpredictable. They are not controllable. The goal of foreseeing the future exactly and preparing for it perfectly is unrealizable. The idea of making a complex system do just what you want it to do can be achieved only temporarily, at best. We can never fully understand our world, not in the way our reductionistic science has led us to expect.

Living systems evolve. 13 billion years ago the universe was waiting to become a molten mass of quantum particles that would expand and evolve into the galaxies and systems we know today. 4.5 billion years ago earth was a molten barren rock flying through space and time; today its home to so many different species we haven’t even counted the ones we’re sending to the sixth mass extinction event. Nothing is so irresistible as evolution, change and ever-evolving complexity.

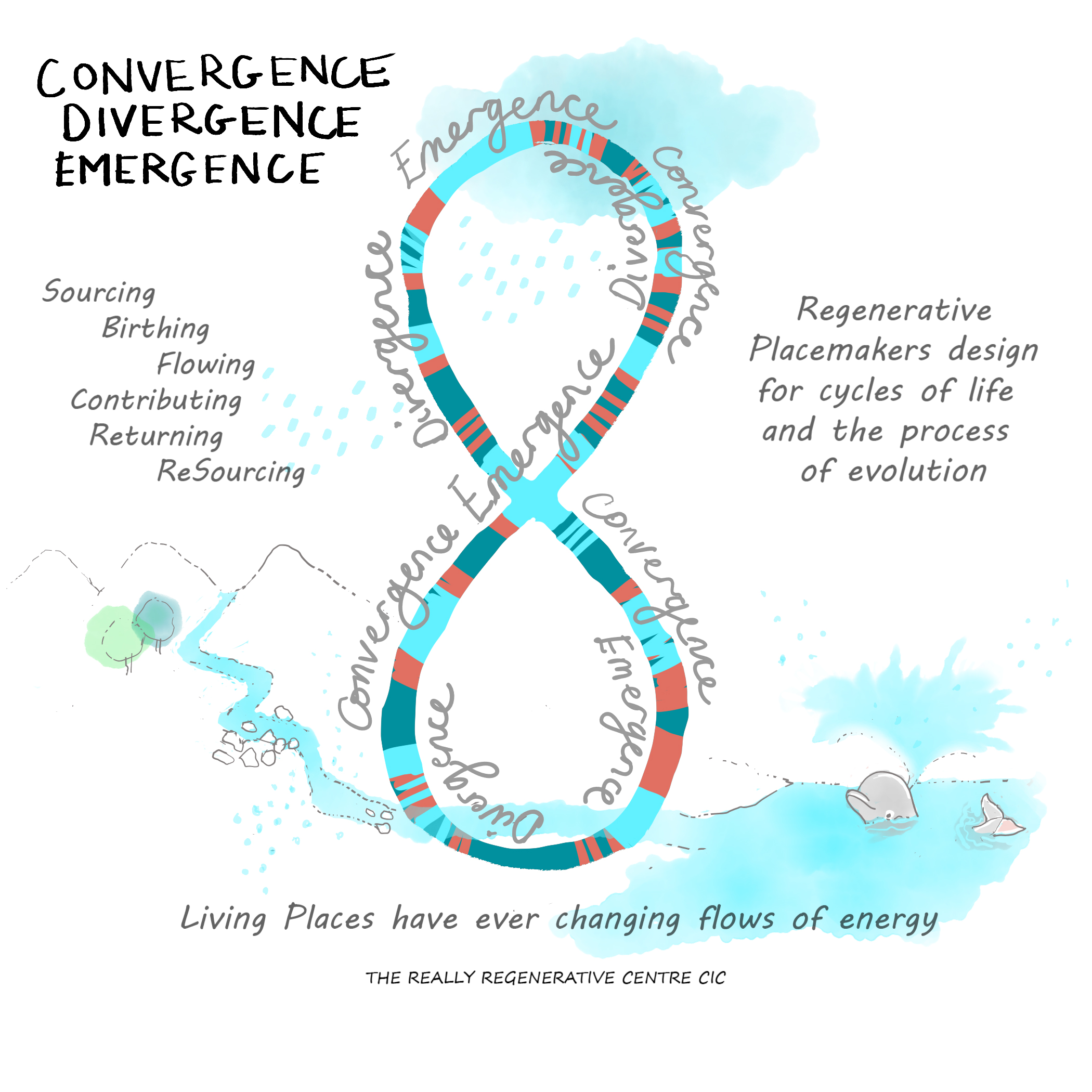

So let’s learn to live well with uncertainty, dance with ambiguity, love paradox. Let’s work with emergence, convergence, divergence in mind – life’s way of constantly evolving; always seeking to create the conditions conducive to life to continue. New ideas, practices, processes emerge; at some point they begin to converge in unity; then they have to diverge again to preserve diversity – one of the core conditions that guarantees life. That’s the wisdom of a living system. Prioritise life – all life, with all it’s inherent unpredictability. Can we find it within us to consider the unknown and uncontrollable, irresistible?

There is a famous international aid story where well-meaning UN project advisers went to Africa to help what they perceived to be impoverished communities grow the finest of Italian tomatoes. Despite local concerns, they planted them on the fertile banks of the Zambezi, knowing they would grow plump and ripe and juicy in such promising soil. Until the hippos came out of the river at night. And ate them all. And the locals just smiled. The visitors had ignored the wisdom of the local system.

Before we dive into the places we’re experimenting on, can we listen first to the local system?

In Kalundborg we prioritised in the first 9 months, listening to the system – whenever we could attract it in. Rather than decide the principles we would experiment with, we indirectly explored what it was that the local system felt was important to them. Over time they lifted up Belonging and the absence of Biodiversity. And became a mini Movement. And only then when we had heard from the system, did we go to work to learn more.

3. Expose your mental models to the open air.

We’re exploring what might be irresistible. Why does one person think about cake, sex and shopping as irresistible, and another think of the universal force of gravity? What do some people see an image in their mind of the pied piper, embodying some quality we all seek and are willing to blindly follow to find? Or others think of addiction, to drugs, alcohol or gambling?

“Everything you know, and everything everyone knows, is only a mental model. Get your model out there where it can be shot at. Invite others to challenge your assumptions and add their own. Instead of becoming a champion for one possible explanation or hypothesis or model, collect as many as possible.”

Today we humans are a highly complex mix of multiple different worldviews, cultures, life experiences, character and personality. Our ideas of how the world works reflects the narratives, ideas and experiences that have shaped our individual lives unless we work hard at self-individuation and sense-making of that complexity. Let’s be patient, compassionate and non-judgemental of our differences, whilst we (or rather Polimi) try to synthesise those variables into valuable and important insights that might change the future.

“Mental flexibility–the willingness to redraw boundaries, to notice that a system has shifted into a new mode, to see how to redesign structure — is a necessity when you live in a world of flexible systems.”

How can we in DESIRE recognise and respect the different mental models that are at work across our community and test and experiment with each other’s models rather than just one that is fixed and immutable?

4. Stay humble. Stay a learner.

If you think you know the answer, you’re more than likely wrong. Working with the vast complexity and awesome intuitive adaptability of living systems keeps me humble. The practice of awe keeps me awake to what I don’t know. As a child I used to stay up late and look up at the stars trying to figure out ‘how big is forever?’ Even with the help of quantum science, the singularity theory, IBM Watson and AI, I can’t answer that question. I try to stay curious in the face of creeping certainty. Every time I think I’m sure, I experiment again with what I think I’m sure of.

As the narratives of uncertain futures populate our media and conversation, humans are reaching for certainties to help them stay sane and grounded. These certainties might manifest as anything from populism in politics to rigid thinking about what is right or wrong to do in the neighbourhood. Staying in a mode of humility and constant learning is challenging in a world that is demanding certainty, simplicity, expertise and instant solutions.

“The thing to do, when you don’t know, is not to bluff and not to freeze, but to learn. The way you learn is by experiment–or, as Buckminster Fuller put it, by trial and error, error, error.”

Sometimes culture makes us afraid of failure. What a culture values, what it gives status to, often directs how we approach work. If we allow ourselves to operate in a culture where failure cannot be celebrated, learned form, venerated even – we can never innovate well. To fail means that you have skin in the game, it means you’re prepared to be vulnerable, expose your unknowing and limitedness – but still put yourself out there to be shot at. If we fear failure, we fall instead into blame and divisiveness as protection against the risk of being labelled a failure. Attack as the best method of defence. If you stay humble and stay a learner, you can learn to love failure as much as success.

How can we embrace the failures we will have, and record and integrate them into our recommendations to the EU? How can we avoid the usual pressure to simply report the positives? Can we be as open about the failures of the bidding process and the flaws in our internal design so that any constraints put on DESIRE through the way in which NEB is structured are faithfully illuminated?

5. Honour and protect information.

Information is power. Or so goes the saying. Maybe this one should be honour and seek to understand the difference between truth, truthfulness and information. Maybe it should be about being humble enough to know that we don’t always get the information we need from the standard processes we use to gather it; that there’s a world of information beyond statistics, quantitative data or even qualitative ethnography. Or that we don’t always recognise what is truly valuable information because it doesn’t fit in a spreadsheet. Maybe it means honouring what’s intuitive as well as what’s rational – or at least finding out how we can learn to trust intuitive data once more.

Honouring and protecting the value of information is also about not withholding insight, information or data. Transparency legislation around the world is great, but what about when we withhold insight and ideas because we think we’ll look foolish, or that people will think we’re batshit crazy, or we just don’t feel we’re in an environment of trust and reciprocity. What gets in the way of trust and reciprocity? Often it’s time: too short a time to build relationships, too short a time to think about how we experiment with communities in reciprocity rather than extraction, using them as laboratory rats.

How can we in DESIRE honour the warm data, the time and the effort our volunteer communities will share with us, ensuring we bring reciprocal value to them at the same time? How can we value intuitive insight as much as standard methods of data capture?

6. Locate responsibility in the system.

Locating responsibility in the system – “intrinsic responsibility” – means that the system is designed to send feedback about the consequences of decision-making directly, quickly and compellingly to the decision-makers. It can be a very radical move, often unpopular in cultures where blame and responsibility is consistently diverted from one potential source to another.

“Designing a system for intrinsic responsibility could mean, for example, requiring all towns or companies that emit wastewater into a stream to place their intake pipe downstream from their outflow pipe. It could mean that neither insurance companies nor public funds should pay for medical costs resulting from smoking or from accidents in which a motorcycle rider didn’t wear a helmet or a car rider didn’t fasten the seat belt.”

How can we experiment with intrinsic responsibility in DESIRE? In Riga we heard from the municipality of Turin on trying to cut red tape in a participatory process with citizens in a way that gives them optionality to act in small ways, putting accountability back into the community system. Social prescribing is a way of trying to move intrinsic responsibility back into the heart of community for its own health.

What might that look like for us in our DESIRE experiments?

7. Make feedback policies for feedback systems.

Donella talked about President Jimmy Carter’s ability to design policies for feedback systems that never got passed because he couldn’t explain them and they therefore sounded threatening and unpopular. Carter was trying to deal with a flood of illegal immigrants from Mexico. He suggested that nothing could be done about that immigration as long as there was a great gap in opportunity and living standards between the U.S. and Mexico. Rather than spending money on border guards and barriers, he said, we should have spent money helping to build the Mexican economy, and we should continue to do so until the immigration stopped. This feels very pertinent right now. But what could it mean for DESIRE?

What are the feedback systems we are seeing in social housing for example?

Flooding or water pooling in urban areas for example, is feedback on both climate change and urban design. Low engagement with work, high rates of absenteeism can be feedback on the unattractiveness of a work environment or culture. Poorly maintained social housing could be a feedback system on our weakening social contract for disadvantaged communities.

What experiments could we design in the second phase of DESIRE that might test policies for feedback systems?

8. Pay attention to what is important, not just what is quantifiable.

What is truly meaningful rarely gets measured in our current world. No one can precisely define or measure justice, democracy, security, freedom, truth, or love for all life. Perhaps no one can precisely define values like belonging or the experience of beauty or awe. But as Donella said “if no one speaks up for them, if systems aren’t designed to produce them, if we don’t speak about them and point toward their presence or absence, they will cease to exist”.

How can we in DESIRE’s experiments speak up and speak out on what is ugly, humanly demeaning, demeaning and unjust to other life, undemocratic, unfair, uncalled for and morally indefensible? How can we speak up for joy unrestrained, love unfettered and the warmth and thrill of coming home to place?

9. Go for the good of the whole.

Wholeness is one of living systems first and foremost principles. The tree cannot be healthy if the whole forest is not healthy. The whole forest cannot be healthy if the watershed it is nested in is not healthy. If those living systems are not healthy, the local sawmills will fail and the furniture businesses on which they depend will also fail. Start by seeing the whole system you’re going to be working with, and the proximate and greater systems it is nested within.

How can our projects explore and enhance the good of the whole of each place? In Kalundborg we asked the question “How can the arrival of the Royal Danish Academy be a catalyst for new potential across Kalundborg?” To achieve that we need to be able to engage with the whole of Kalundborg, putting an extra emphasis on diligent stakeholder mapping. It’s also helpful to realize that, especially in the short term, “changes for the good of the whole may sometimes seem to be counter to the interests of a part of the system.” Resistance, difference of opinion, will arise.

What are the capabilities we need to design experiments that are fully and wholly inclusive? How do we engage all parts of our place, leaving no one behind, not even the silent voices who cannot speak for themselves?

10. Expand time horizons.

We may have only 2 years to work on DESIRE but all actions we take, at any time, can have reverberations which last much longer than a random period of time we are allocated. . First nations and most indigenous peoples have a different relationship to time when planning. Everything is considered with seven generations into the future in mind.

In the effects of extreme weather events, we are experiencing the consequences of actions set in motion decades ago as our fossil-fuel energy system expanded. The circular economy itself is a response to arrest disorder in the system of extraction and consumption which hopes to leave more material in the ground and recycle and reuse what we have already extracted or made.

Even though this is a very short pilot, can we design our work always with an eye to future generations and how this project may unfold in the future?

11. Expand thought horizons.

“Seeing systems whole requires more than being “interdisciplinary,” if that word means, as it usually does, putting together people from different disciplines and letting them talk past each other. Interdisciplinary communication works only if there is a real problem to be solved, and if the representatives from the various disciplines are more committed to solving the problem than to being academically correct. They will have to go into learning mode, to admit ignorance and be willing to be taught, by each other and by the system.”

If I have a brain tumour, I want a surgeon to operate on me who is a specialist and an expert in brain surgery. But if I want to find insights from a complex adaptive system, then I want the wisdom of the crowd and polymathic input, not subject experts with narrow lenses and biases. Can we open up to new sources of warm data and take them seriously? Children. Young people. The voice of nature. Can we experiment with other sources of ‘knowing’ like intuition, patterning, storytelling experience as well as empiricism?

However time-consuming, our peer to peer learning programme will be invaluable if we can all keep our minds open and follow wherever the systems we are working in lead us with open, non-judgmental minds. How can we remain willing to learn from each other and stay committed to creating truly valuable new insight, even if that means diverting from (and therefore being able to explain why) the mandate given to us by the EU?

12. Expand the boundary of caring.

In regenerative design we’re always trying to show systems to themselves. The interconnection and interbeing they can’t see. We lift up stories of place, patterns of place, relationship to place, to the people and life within a place. Every time we ask a community to look at the way in which patterns play out in ecology, culture or economy, we’re inviting people into a field of caring about the place they inhabit. We’re trying to heal the story of separation. Between humans and nature. Between humans and humans. Between the value we have given to our analytical, rational left brain over our connective, creative, compassionate right brain. To bring us back into balance. We act for what we care about. If we can reignite a field of caring for the places we inhabit – place by place by place – we can heal the divides between us and in the process, go a long way to stabilising the planetary boundaries of our life support systems.

DESIRE originated in Denmark. Some time ago I read two really interesting books on Nordic cultural and economic design. The Nordic Secret by Thomas Björkman and Lene Andersen, and Economies That Mimic Life by Harvard professor Joseph Bragdon. In both they tell a story of the impact of creating cultural circles of belonging, as well as designing economies based on the bio-cultural uniqueness of the Nordic countries. I found both very insightful.

In exploring cultural circles of belonging we can ask: how can I value and contribute the people and nature where I live? How can the place I live contribute to the thrivability of my country? How can my country contribute to the thrivability of the world?

Living systems are nested systems, relating to each other. Circles of belonging are like stabilising nets of a mangrove swamp. They share the nutrients across the edges of different systems and connect them together. They connect ideas, peoples, places, and life.

How can we bring new fields of caring into being in DESIRE?

13. Celebrate complexity.

I confess to being a complexity geek. When other people throw up their hands in horror at complexity, my nostrils twitch, my eyebrows start to waggle with excitement and my eyes twinkle with anticipation. We live in amongst complex adaptive living systems. They are unpredictable and uncontrollable, but they make life work. We wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for complexity.

We ourselves (individual humans) are complex adaptive living systems. Thanks heavens for a respiratory system that adapts as I swim to take in more oxygen and moves it round my circulatory system into my muscular system so I don’t get cramp and sink. Thank the stars for the mycelium we can’t see that moves nutrients and water around the soil so our complex adaptive forests stay healthy and nourished. Thank the unfolding, expanding universe for the miracle of Gaia, from her journey from a single celled life forms 3.8 billion years ago to the unimaginable brilliance of teeming oceans (not quite as teeming as they were), buzzing rainforests (unfortunately now buzzing with chainsaws), the billions of bacteria in my gut that busy about and process the over-rich, over-sized plates of food I’m tempted on occasion to eat.

Donella’s wise words: “There’s something within the human mind that is attracted to straight lines and not curves, to whole numbers and not fractions, to uniformity and not diversity, and to certainties and not mystery. But there is something else within us that has the opposite set of tendencies, since we ourselves evolved out of and are shaped by and structured as complex feedback systems. Only a part of us, a part that has emerged recently, designs buildings as boxes with uncompromising straight lines and flat surfaces. Another part of us recognizes instinctively that nature designs in fractals, with intriguing detail on every scale from the microscopic to the macroscopic. That part of us makes Gothic cathedrals and Persian carpets, symphonies and novels, Mardi Gras costumes and artificial intelligence programs, all with embellishments almost as complex as the ones we find in the world around us.”

How can we avoid wanting to simplify too much in our short pilot in order to get things done? How can we avoid the risk of returning data that is too reductionist? How can we honour the complexity that we are working in? Does it mean less and deeper? More systemic understanding and less doing?

14. Hold fast to the goal of goodness.

I believe we are good people. Even in the depths of despair at what humans can do to other life and to each other, I believe our fundamental hearts want to do what’s good in the world. Despite our fears, our egos, our vulnerabilities, our inability to manage our state, our reactiveness and our blind spots, if we keep on calling out and recognising goodness, we encourage more of it.

We’re in a battle for our attention, and what grabs the headlines is bad news. Murder. Accidents. Wrongdoing. Extortion. Moral failure. Cancel culture. Is it any surprise that many people think the world would be better off without humans? Bullshit. We have a role to play here on planet earth for as long as we’re here, we just need to remember it and then build the will and capability to do it. We’re here as catalysts for life; to help this beautiful planet continue to create the conditions conducive to life.

How can we, the whole hearted of DESIRE and the New European Bauhaus, draw out goodness in the future of the built environment and celebrate our alignment with life as stewards of our living systems?

Recent Comments