FROM EXTRACTIVE TO INTERCONNECTED ECONOMIES

Activating Citizen Democracy

In Donella Meadows paper Interventions in Systems, she writes about buffers and stocks as stabilising forces in society. Mostly when we think about buffers and stocks we think about things like water reservoirs which hold excess rainfall and are used to serve the population in a region in times of drought. Or the stock of pasta and rice in our food cupboards. Or the stocks large retail systems hold to be able to adapt to mini crisis such as lorry blockades and delays in the transport system from one country to another — as we have recently seen during the pandemic and as part of Brexit in the UK.

Healthy working democracy is also a buffer against the rise of autocracy and populism. It’s a buffer — that we can see in recent years with the rise (and now fall) of Trump, with the experience of Brexit, with the growing polarity and strength of both the alt left and alt right in politics — that is breaking down and allowing more and more polarity and duality into national and international narratives.

Can democracy really deal with the existential challenges of climate change and biodiversity collapse, and the ricocheting emergencies that these are throwing at us — from pandemics to polemics? When we often have narrative ‘evidence’ in public dialogue to suggest that more autocratic regimes, such as China, have greater ease to deal with emergencies through autocratic rule than democracies seem to have?

Without turning this into a full blown book on democracy, let me see if I can make a few salient points.

First another really quick zip back in history. The Ancient Greeks are mostly given credit for the design of democracy. Scholars like Solon, Aristotle and Pericles aimed to shape politics, economics and society based on a collective endeavour, compromise and consensus. Their goal was to design a form of government in which ‘the people’ have the authority to choose their governing legislators, and where important pillars of a democratic infrastructure include freedom of assembly and speech, inclusiveness and equality, membership, consent, voting, right to life and minority rights. Foundational to its successful functioning was discourse and the use of collective intelligence.

Aristotle — “Common people deliberating can arrive at better decisions rather than philosophers acting alone.”

Pericles — “Discussion is never a stumbling block. It is always an essential prerequisite for any wise action.”

Different forms of democracy have emerged in successive western civilisations — Greek, Roman, modern Europe — including

- representative democracy where politicians are elected to run the country on behalf of the people

- deliberative democracy where laws are formed through a process of rational debate

- participatory or direct democracy as supported by Aristotle, Gandhi and Rousseau which ranges in form from Marxism to liberalism

- grassroots democracy as supported by Ranciere, Habermas, Rouffe and Laclous — although to be honest I’ve never really understood the difference between it and participatory

Most global economies are representative democracies in some way. So what has gone wrong with those democracies and what might need to change if we are to achieve regenerative economies in the future?

It’s important to acknowledge that current political systems also have a collective responsibility for the mind-blowing levels of polarity and inequality in our social systems. They have played a significant role in allowing the laissez-faire economics that has created our ecological crisis through its extractive, degenerative processes, to the point where the planetary system, our social systems and our economies are in crisis.

Politics is our collective decision-making system. Global business influences — often far too much through un-transparent lobbying systems — and executes against those decisions. We all have a collective responsibility for allowing the capture of those two systems by a small group of highly dysfunctional individuals who have amassed power, privilege and wealth and trampled on all other human and non-human life interests in the name of freedom and progress. Yet we are struggling to exercise the potential of citizenship to create a fair and just future.

It is clear that this model is running its course. We cannot continue to exist on a finite planet in a system of constant degenerative extraction.

The roots of colonialism

Our existing political systems find their roots in the mechanistic mindset we described in Part 4 of this series, but they also find their roots in the human experience of that mindset. The ruling political class of the post-Renaissance era embodied a hierarchical control agenda which brought massive scientific and industrial breakthroughs to the world raising millions out of poverty, but also had some significant downsides such as enclosure of the commons and global colonialism.

Colonialism breaks the psychology of both the oppressed and the oppressor. In Europe we learned how to do this through a massive land grab of the commons, and by regular invasion and dispossession of our own national and cultural groups. Long before Europeans set sail for the new world, they had practised the art of enslavement and oppression on themselves.

Colonialism forced large swathes of the world to comply with their new rulers, by adopting a new set of cultural norms that often went completely against what they believed in and had lived for generations. The design process of colonialism was to dehumanise, degrade and limit the ability of populations to resist by destroying any personal sense of agency, and then to set in place a system of internal competition which set tribe against tribe, people against people. All of which could take place whilst the colonialists extracted great wealth at low cost and shipped it back to Europe.

Colonisers have to sever from their own innate empathy, sensitivity and sense of their own decency in order to be able to control the supposedly ‘inferior’ colonised.

One of the kickbacks of colonialism is the psychological damage it also inflicts on the perpetrator. To subdue and dehumanise other people, you have to dehumanise and subdue your own finer sensibilities. Your own humanism. EVA SCHONFELS/JUSTIN KENDRICK, Transition Network

And so over generations — again a quick reminder, as we think so we design — our political systems became run by an elite group who were accumulating their own de-humanised view of the world — and gradually building inter-generational trauma into their descendents.

In the UK we see this play out in our public education system which consistently produces politicians devoid of understanding of their fellow humans. We see it in the pugilistic power of the despatch box in the House of Commons where one leader is pitted against another in a point-scoring extravaganza that does nothing to serve the will of the people. People who learned how to destroy the cultural and spiritual fabric of the lives of other people half way across the world, inevitably brought back and embedded the same structures into politics and business. Where there is no possibility of empathy and external consideration of the ‘other’, there bullying, oppression, and public shaming thrive as tools of control.

As Eva Schonfeld and Justin Kernigk of Transition Movement write: “This energised a massive negative cultural feedback loop: traumatising individuals and communities, seeding in them the potential to become dominators, ensuring that the indigenous cultural processes which could have supported healing and recovery were also systematically destroyed. Connections with local spirits were demonised, spirituality privatised, childcare put into the hands of the state, pupils kept indoors and alienated from the wisdom of their bodies, displays of any empathic emotions repressed, elders forgotten, lands held in common stolen, and people forced from subsistence livelihoods and a connection with family, place and nature into slavery or wage slavery, whether on plantations or in cities.”

So. How do we combat this multi-generational trauma? That’s too big a question for this section of the paper, but in terms of democracy it’s time to look again at participatory or grassroots democracy.

The rise of deliberative democracy

Across Europe we have seen the rise of deliberative and participatory democracy through many movements in recent years. From the post 2008 anti-austerity movements like Occupy, to the more recent pro-democracy movements in Thailand and China, to the rise of Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion, large population groups are continuing to advocate a return to a more participatory form of democracy.

Extinction Rebellion’s initial call for citizens assemblies has been met with encouragement in local authorities across Europe. None have embraced an outcome that is more than advisory yet (control must be maintained after all), but the experiments with citizen participation in climate assemblies is helping to galvanise collective vitality towards an agreed approach to designing local net-zero economies that are shaped by the people that live within them. They may be clumsy and experimental as yet, but with each assembly learning is shared across a wide network of organisations that seek to continually improve the process.

Learning how to Share

Participatory democracy is also fundamentally about re-learning how to share; in a myriad of different ways.

- How we share not just resources, but ideas, knowledge and learning. We’ve seen this emerge through the Creative Commons licence for example, but there is still incredible tension around how to generate good livelihoods when you give away freely the knowledge and practice you have learned over a lifetime. A service economy with a high level of consultancy is going to struggle with this transition. It has implications for trademarks, copyright, intellectual property — some of the bastions on which a competitive capitalist economy is based.

- How we collaborate instead of how we compete. To work out where and how competition works beneficially in a society more dedicated to equality instead of how it is used to accrue personal wealth and power.

- How we hold difficult conversations without punitive rancour. If we focus on the future potential of people and place, can that help us learn to discuss difficult issues without the sense that there will be a loser and a winner — the zero sum game of the market.

- How do we work together through these challenging times by designing win-win-win ways forward that are not dependent on compromise or consensus of prevailing economic thought and diplomacy.

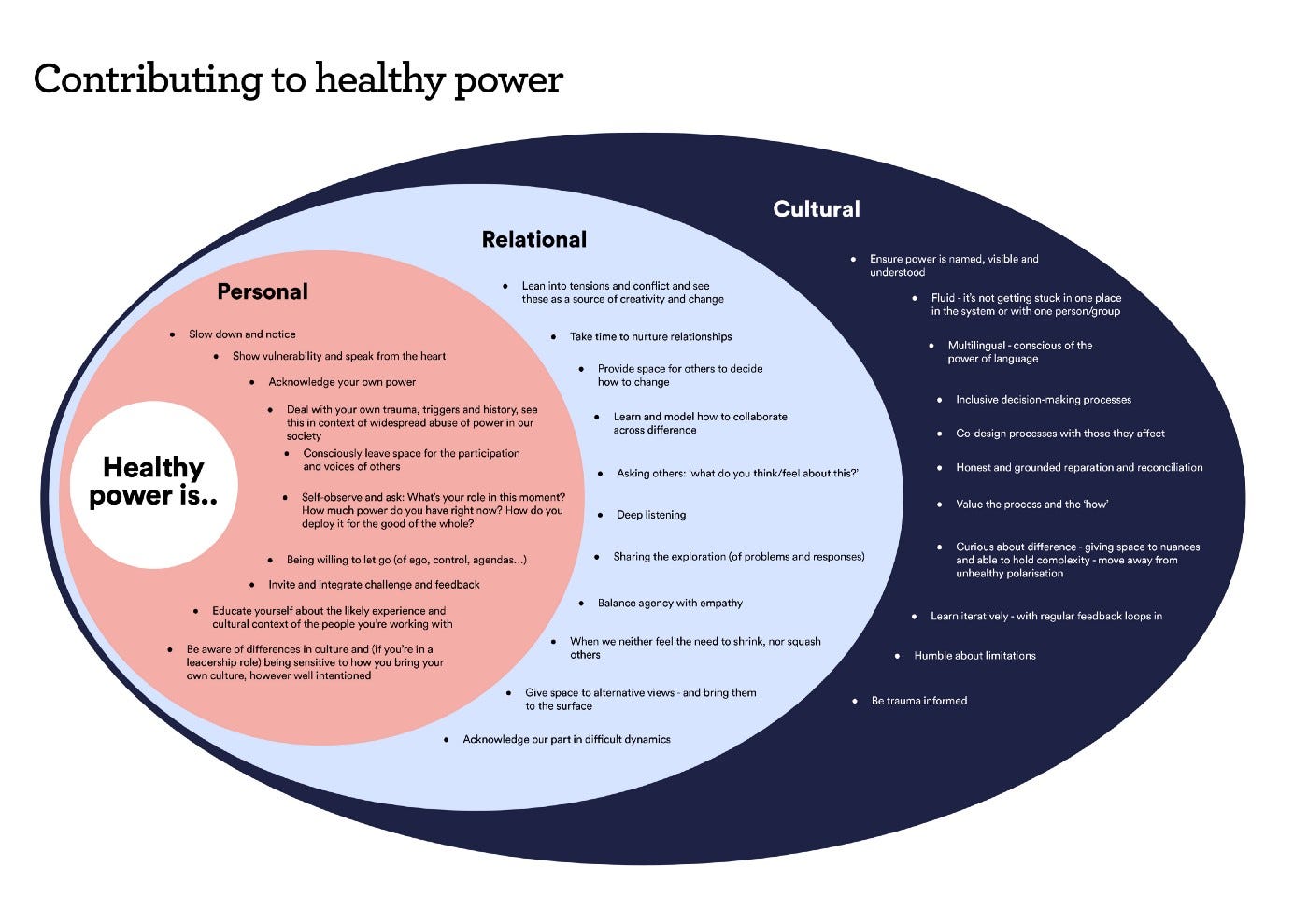

- How we design for healthy power. Healthy power was the subject of study for the group in which I participated in the Boundless Roots enquiry. Of our key findings we noted that we need to name and rename power in our messaging and embody healthy power in our relationships, and invest in process leadership to design and facilitate healthy power. This includes funding shared governance and decision-making processes, embedding healthy power in the education system, investing in learning between funders and practitioners to build healthy relationships, especially to money.

- How we learn to allow the highest potential of our people and places to emerge. This is about creating a deliberately developmental economy and education system (see Part 9) but also at the individual and organisational level, about learning to share airtime with others; not always self-promoting, not rushing to step in with your own opinion and point and instead, choosing to be someone who creates space for others to shine — at least some of the time.

- How we share things; from cars to property to land to clothes to just about anything you can think of. The sharing economy goes hand-in-hand with a reduction in production and manufacturing and is an important part of the circular economy — a strategy to slow down the impact of extraction by reusing what already exists. It also heralds a whole new look at Ownership — especially of the Commons.

The Economy of Place is a series of articles by Jenny Andersson that are edited parts of her unpublished book Renewal. There are 20 parts to this paper which will be published here in due course. If you would like early notification of future releases, please register at Really Regenerative — Economy of Place.

Further reading:

The Boundless Roots Report

Politics, Trauma & Power, Eva Schonfeld & Justin Kenrick

Democratising Democracy

White Supremacy Qualities

Daniel Schmachtenberger’s video on The War on Information

Scotland’s Climate Assembly Interim Report

Recent Comments