HOW DO WE CREATE REGENERATIVE TOURISM DESTINATIONS?

Although we haven’t quite yet finished the part of this series which looks at key issues that help us shift from extractive to interconnected economies, the time has come to take a sideways shift to look at some specific industries. We will start with tourism as last week saw one of the most ground-breaking studies published — We Are Aotearoa — the vision for regenerative tourism for New Zealand.

The tourism industry is a sector that has been more affected than most by the covid19 pandemic. Previously one of the world’s biggest contributors to GDP, overnight cruise ships weighed anchor, hotels closed, flights were grounded. The entire infrastructure of global tourism came to a halt. Although the infrastructure of tourism that moves people from one place to another has a huge impact in itself on the stability of our planetary ecosystem, this article focuses most on the places they arrive at and the how to increase the potential of people and place in each destination.

In an earlier article we noted that the existing economic model for destination management is numeric. The aim is to grow footfall, per capita spending, contribution to GDP, and increase jobs. There is very little consideration given to the needs, impact on, or benefits to the local host population, and there are no measurement systems in place to look at the potential for increasing the wellbeing of the people and businesses in a destination. As a strategy, you could argue that increasing visitor numbers has been enormously successful, but it has left a legacy system which regenerative tourism specialist Anna Pollock describes as one in which ‘destination managers have to work with a (mal)adpative mix of brands, venues, amenities, agencies, people and businesses, which exert a significant impact on the local environment and infrastructure’.

As one of the most advanced nations when it comes to regenerative economics and social innovation, this week New Zealand published its future strategy for regenerative tourism — We Are Aotearoa. Designed over a 6 month study period, this ground-breaking report showcases for the first time what an approach based on living systems thinking could look like — and I’m happy to say minus any jargon whatsoever!

It demonstrates what can be achieved when living systems principles are subtly embedded in the way in which a diverse group comes together to work holistically on future vision and strategy. This is probably one of the most seminal pieces of work done in the tourism industry for a long time.

What does tourism, designed as a regenerative living system that considers the deliberate development of potential for people and place look like?

I will try to pick out some of the We Are Aotearoa key fundamentals but also showcase a few other projects from around the world. Needless to say, the hand of Anna Pollock is in many of these.

1. Designing for WHOLENESS

You’ll notice in the New Zealand report that the word ‘whole’ appears frequently. That’s no accident. Designing to include the whole of anything — but especially a tourism destination or region — is a fundamental step away from focusing on single group or silo issues. Like footfall numbers. When we consider a whole living system it is brought alive by all the different players working in harmony for the collective benefit of everyone. It’s language and attitude is collective:

We are all hosts. We are all visitors. We are all part of the tapestry of cultures and identities that connect us to each other, to Aotearoa New Zealand and to the world. We are the team of six million storytellers — both those living in Aotearoa New Zealand and the diaspora.

It is no small task to bring together an industry of diverse needs, businesses and individuals and design for wholeness. Wholeness is formed through a complex mix of qualities and practices which emerge through the fingertips of careful hosts and facilitators. It is formed through dialogue without rancour, vision of future states, tapping into the energy & flows of cultural and biological patters for change, all set within context. It is held by respect, compassion, consideration for one another, caring and above all a resolute determination to bring life centre and front in an industry that has all too often forgotten about life and plundered it instead.

2. Following Indigenous Energy Flows & Patterns

I’ve written several times in this series about the importance of energy flow and patterns of nature. Every unique place and living system has its own unique rhythm. A beat to which it responds and which creates a thriving, vibrant whole — unlike any other place. To feel that incessant beat, to tap into that rhythm requires careful attention, listening and observing. It requires research into the past, sensing into the present and seeing into the future. It’s also very practical and looks at the patterns of how people do, and have, inhabited this place.

It helps of course if you can tap into your place’s indigenous wisdom. We are all indigenous to planet earth, but in some special places in the world, indigenous wisdom has been preserved — despite the attempts of western civilisation to eradicate it. Both the New Zealand taskforce and the report were inspired by the Te Ao Māori perspective. The use of the Tāniko patterns was chosen as an important visual enrichment throughout the report.

Each of the Tāniko patterns was chosen as an important visual symbol throughout the report and illustrates the importance of symbolism to connect narrative and soul of any project. ’They symbolise the weaving together of perspectives, priorities, ideas and stories that bind us together as a whole industry and nation. The specific patterns chosen relate to the Future States we are envisioning and working towards with this report. They represent significant actions and consistent focus on key parts of our tourism ecosystem to ensure the change needed is achieved.’

Pātiki = industry thriving, the conditions needed for industry to thrive

Waharua kōpito = Te Taiao regenerating, tangible commitments to take care of the environment

Niho taniwha = Empowering communities

Taki toru = Aotearoa Whakapapa, community, connection & culture at the heart of tourism

Purapura whetū = navigating our future, data dand insights to navigate future pathways and strategies

3. A Bold, Brave Vision of the Future State

In regenerative development, we always work towards a future state which we envision together. The future state is a powerful vision which sets the end state to which any group chooses to work towards, supported by key pathways which help keep the vision on track. We do this while recognising that the pathways are not straight and simple, but complex and constantly shifting with context and circumstance. Nevertheless, the future state is what gives a project its vocation, its vitality and keeps the team together when the going gets tough — because it has been developed together, and it is walked together.

We are Aotearoa’s vision statement:

Enriching Aotearoa: Nourishing people and place. Enlivening communities and culture.

We are here to nurture this place, enriching generations with livelihoods, experiences and stories to share. We must own the impact of our actions and enable Aotearoa New Zealand to thrive by giving back more than we take.

Of course it helps any tourism organisation if its vision and future state chimes well with the national government strategy, and is reflected in other departments. It takes a very bold organisation to step out on its own, but it can be done with courage, visionary leadership and step by step — without being rushed by the pressure of time, or the current pressure to reignite the tourism economy.

In New Zealand leadership bodies from the finance, primary and conservation sectors, as well as central and local government and Māori tourism had already set the future visions for their respective areas which correlate strongly with the tourism vision presented in the report. Additionally the context of the Government’s Wellbeing Agenda, provide a strong mandate to make the bold changes recommended by the Taskforce.

4. Designing for a Different Kind of Growth

If we recognise that the existing tourism system based on footfall and GDP is having a deleterious impact on people and planet and it isn’t in fact increasing the wellbeing of people or the flourishing of other life in place, we have to first imagine a different kind of system, a different kind of visitor economy. An economy that considers a different vision of what growth is and measures different values that can replace volume growth.

A living system is made up of many different species that contribute to their own growth, to that of others and to the overall health of the whole system, creating resilience, adaptability, and sustainable growth. That indicates that we need to consider what it would take for all the contributors to the visitor economy to thrive and contribute so that a net benefit to themselves and their place is achieved.

A regenerative economy means developing an operating model that optimises benefits to all stakeholders instead of maximising the benefits to a few shareholders. This means the needs of the individual (employee), business, community and environment must all be met within a design which is in balance with the natural environment. It means moving from volume to value and quantity to quality.

Valuable questions to begin with include:-

- How can we design a tourism economy in which all people in this place thrive?

- How can we design a tourism economy in this place which thrives in partnership with its natural habitat?

- How can we design a tourism economy for this place with due respect the wellbeing of people worldwide?

- How can we design a tourism economy for this place which respects the wellbeing and health of the ecosystem, bioregion and whole planet?

Designing for a different kind of growth also means setting very different metrics to measure qualitative regenerative value. Elke Dens of Visit Flanders is one of the pioneers of regenerative tourism. She’s been a champion of a shift in paradigm towards an “economy of meaning” where economic growth is no longer the ultimate goal, but flourishing for all contributors, is.

At Visit Flanders for some years they have been consulting with the whole host community to gradually change the offer of the region from a quantitative to qualitative model, measuring the wellbeing of the hosts and visitors in the economy. The recent Van Eyck exhibition in Ghent during the covid19 lockdown was a great success It incorporated a ‘Museum at Home’ with interviews with curators and online tours for those people who couldn’t visit, and an experience for those who could which research showed was completely enhanced. Although they wore masks and had to queue, the additional space to contemplate and enjoy in a less crowded environment where lines in front of exhibits are often 10 deep, was clearly appreciated.

It also means bringing the whole community together that contributes to the visitor economy and working together to lift up a new vision that delivers a much more compassionate, caring and connective experience that offers regenerative value to both host and visitor, and lifts up the potential for all life to flourish in place.

We have lost sight of the potential for tourism to activate the highest human values; to offer the opportunity for connection that we are wired to deeply desire, and to offer a change to develop, deepen and evolve our experience of the world to a more inclusive, compassionate and caring learning journey; to be able to contribute to a meaningful future for all ilfe, and to lift up our potential to be good ancestors.

We need to create collectives or guilds that encompass all the ‘capitals’ represented in our place; natural, social, economic, financial, and human, with rotating representation from different stakeholders in a self-organising, co-creative system that continually refreshes and evolves according to the developing needs of the community of practice in its place.

Visit Flanders is once again a great example here. Elke Dens has been a key advocate for the inclusion of the local community. Visit Flanders works within a virtuous circle found at the nexus of visitors, local residents and business owners who are recognised as hosts, with an aim to develop its unique potential and contribute to the health of the whole.

“The goal of flourishing is a critical aspect of regenerative travel that is a quantum leap beyond sustainability. ‘Flourishing’ is a term developed both in positive psychology for human beings and in ecology for all life forms. It therefore has both a human/psychological/well-being/performance dimension and an ecological, systems health dimension. It is easy to understand when you talk to people.”

- facilitate the expression of the unique bicultural potential of your place, involving all the host stakeholder groups, giving the voice of nature a chair at the table create a new framework for growth that is not dependent on footfall and GDP

- explore and lobby for new funding models that match the new framework

set up measurement metrics that account for the thrivability of people and nature in place, and the impact on people and nature in the nested system

involve the whole community in developing this qualitative model through inclusive, self-organising guilds - co-creatively develop a future state vision towards which to work, designing adaptability and agility into the journey towards the future

5. Designing Collaborative Community

We’ve seen that living systems are collaborative and strive for mutual wellbeing for all living beings in the system, and the system itself. In a destination this means finding ways to allow the whole local community — all the stakeholders — to come together and express their own vision and needs for the economy. Working together in community together to image a future vision where people and place, visitors and the wider environment also thrive, often means developing new skills and qualities. It means actively choosing to design and environment in which both hosts and visitors have the opportunity to learn and develop, together.

For many decades our economic operating system has been competitive rather than collaborative. One hotel competes against another, one attraction against another, for the all important footfall and spend. Finding a design for any destination that creates value for both people and environment demands a deep understanding of both the carrying capacity of the place and the ecosystem and infrastructure within it. It means thinking about, and working closely with, infrastructure organisations like water and transport, to ensure that our systems of supply can continue to thrive within the demand created. This is not possible in a number-driven economy; only within a design of collaborative thriveability.

Creating collaborative community also necessitates having and hosting sometimes challenging and difficult conversations; finding ways through what might appear to be conflicting needs to find the optimum potential for the whole system. Creative community vitality depends on being able to express a collective future vision towards which everyone works towards, with the agility and adaptability to weave around interim goalposts when conditions change.

This means that destination managers need wholly new skills. They need to be warm and welcoming hosts of conversations; they need to be able to facilitate the emergence of a cohesive vision from a diverse group of people with different needs and pressures. They need to become adaptable practitioners who can sense into the energy emerging and hold space for it to flourish with courage, caring and compassion for everyone. They need to become agents of change. And at a time when people are more fearful than ever that their livelihoods are disappearing in front of them.

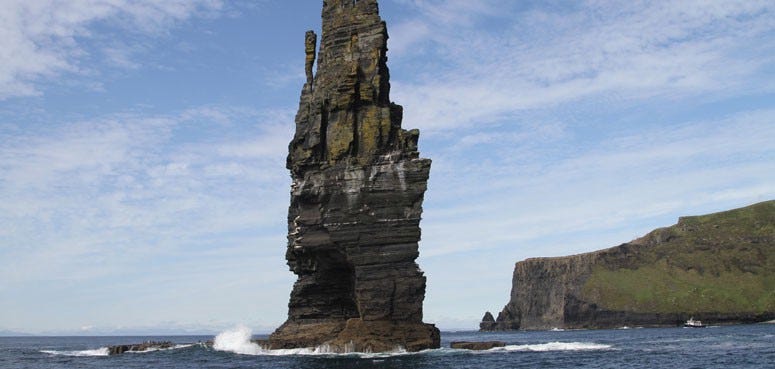

The Burren Ecotourism Network in Ireland epitomises this community approach. In 2008 the Burren Connect Project first established a network of people and small businesses working in the area and agreed to collaborate, pooling their resources in pursuit of a common objective of establishing The Burren as a premier ecotourism destination in Ireland. Together, they work on developing a model of tourism that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people. They work together to promote ‘The Burren & Cliffs of Moher Geopark’ as a leading sustainable visitor destination, celebrated for high standards in visitor experience, conservation, and learning. It seeks to support continued training and mentoring in sustainable tourism for its members and for businesses interested in joining the Network.

- focus capacity building for destination management on facilitation, collaborative design, hosting conversations, systems thinking

- design opportunities for capacity building for facilitation, collaborative design, hosting conversations and systems thinking in the host stakeholder network

6. Designing Developmental Experiences

Encounters in nature are joyful, mutual and meaningful in every sense of the world. What has often been presented to us as ‘raw in tooth and claw’ in nature programmes, is never without meaning for the ecosystem we are watching. The migration of the wildebeest herds across the Serengeti are meaningful for the grasslands of both the Seregenti and the Mara as the herds provide nutrients to the soil as the travel, food for other predators like crocodiles, lions and cheetahs. The flight of penguins from a hungry sea lion is nature’s way of keeping a balance of species in an ecosystem.

Regenerative tourism expert Anna Pollock describes this as enhancing and enriching the source of value that comes from the encounter between visitor and host when some form of value exchange occurs. “Such an exchange could be as fleeting as a smile, a significant investment of money, the decision to return and invest, or a deeply personal sense of meaning, wonder or purpose that leads to a shift in personal awareness or belief.”

For some time we have operated in a knowledge economy. There’s now an opportunity to shift to a deep learning experience economy. Destination managers should start to consider working with hosts to join the dots between opportunities to develop the potential of visitors to their places. We’ve seen this already in many small destinations that are adding learning journeys to their experience economy.

Sustainable farmers Dodgson Wood in the Lake District recently received funding to build an outdoor learning centre so that they can deliver learning experiences for those who are interested in regenerative farming. Cookery schools like River Cottage in Dorset England, Ballyknocken in Ireland, Wiston Estate in Sussex have all branched out into the knowledge and learning economy along with thousands of others. But what if they added a really developmental and regenerative aspect to their offers?

Of course not all small businesses can afford to invest in facilities and their own development to help this developmental economy arise. So we need local and national governments and economic partnerships to look at different measurements of growth and fund different approaches to creating qualitative, developmental economies. And we need first to recognise that human development runs side-by-side with the natural development and potential of place.

On an island in the archipelago off Stockholm, entrepreneur and regenerative visionary Tomas Bjorkman hosts learning journeys for young people. The island of Ekskaret is the place in which Tomas has reintroduced the concept first discovered by leaders of the Nordic nations at the turn of the 20th century. In his book The Nordic Secret, Tomas tells the story of the academy system set up across Sweden Norway Denmark and Finland with the goal of taking a minimum of 10% of young people through a year’s developmental journey to change the psychology of the nations from a poor agrarian economy to a flourishing modern economy. The rest, as they say, is history.

What if tourism destination managers worked with attractions, venues, and the local educational economy with the aim of not just entertaining people in the short term but changing the way they view the world in the long term?

- adopt a deliberately developmental approach to destination design

- foster a deep learning economy in which all stakeholders have an opportunity to fulfil their true potential

- increase value to the ecosystem and people in place through revitalised experiences that lift up the highest human values

- design restorative and regenerative experiences that revitalise both humans and place

7. A New Bio-Culturally Unique Narrative for the Journey

We are all on a journey towards a new economy whether we like it or not. If we hold close the experiences of covid19, we know deep in our hearts and souls the peace we found in the silence and stillness of the cessation of our thrumming world, brimful of activity that leaves us no time to stand and stare.

At the heart of a regenerative economy is a new expression of what it means to be here. Here on the only planet we know in space and time that has the gift of life. Here in our place, our destination which has a unique potential to express its biology, ecology, geology and culture in an invitation to visitors from hosts that is rich with compassion and bubbling with revitalised life.

This requires a new and novel understanding of our place. Of what is truly unique about us, and not a homogenous mix of global imperatives. It requires us to much more deeply understand who and what we are. To look at the patterns of place over time and age to know the indigenousness that is solely the perquisite of here. To sense into what the soul of this place wants to express and offer to the world. That’s not a world of Disney destinations, tatty tourist trinkets, or a homogenous high street that looks like it could be anywhere in the world. It’s about deeply digging into the developmental role that you, your project, your place can play inside your unique ecosystem.

What is its contribution to the future? How does it deliver that in its own, incomparable way? It’s not just a snappy strap-line conjured up by a brand or marketing agency; it’s the expression of people, place, plants, wildlife, geography, geology, biology and culture that is fundamental who you are in the world today and what you want to contribute to its future. It can only be expressed through careful, considerate, facilitation of conversations that allow that story to rise to the surface — from the people and life that inhabits that place.

I’ll finish with the beautiful narrative that has emerged for the We Are Aotearoa project:

Enriching Aotearoa

Nourishing people and place. Enlivening communities and culture.

We are here to nurture this place, enriching generations with livelihoods, experiences and stories to share. We must own the impact of our actions and enable Aotearoa New Zealand to thrive by giving back more than we take.

We are tourism

We are all the future visitor economy of Aotearoa New Zealand. We are all hosts. We are all visitors. We are all part of the tapestry of cultures and identities that connect us to each other, to Aotearoa New Zealand and to the world. We are the team of six million storytellers — both those living in Aotearoa New Zealand and the diaspora.

We have Mauri — we carry a life force that connects all living things. Our Mauri is what binds us to the land. We are a visitor economy that contributes to the wellbeing of New Zealanders — socially, culturally, environmentally and financially.

We are the businesses and employees that enrich our visitors and our communities simultaneously through our unique expression of Manaakitanga (hospitality), Whanaungatanga (connecting people to people) while acting as Kaitiaki (guardians and stewards) of our people and places.

Further reading:

Travel to Tomorrow — blogpost by

A conversation between Anna Pollock, Elke Dens, Tina O’Dwyer on the opportunity of regenerative tourism

We Are Aotearoa — The New Zealand government’s approach to Regenerative Tourism

Can tourism be regenerative?

Recent Comments