We are in a time of breakdowns and breakthroughs. The experience of the global covid19 pandemic has cast a bright light on the frailty in our global economies, has highlighted our inability to adjust to complexity, uncertainty and volatility, and accelerated the conversation about what needs to change in our world. Not just to adjust to the possibility of future viral anomalies, but to the greater challenges following in its wake.

Climate change. Biodiversity loss. Soil degradation. Ocean acidification. Economic and social collapse.

We know that these challenges are driving deep systemic change. It’s no longer a question of why we have to change, but how. This series focuses on a key aspect of how we design regenerative economies to address the imbalances in our current thinking — the economy and power of place.

Today’s global economy is fundamentally designed to foster constant growth. Constant growth requires constant extraction. Of natural resources, but also of hope and meaning from the people trapped within it. Constant growth on a finite planet under existential threat, mainly caused by the extractive nature of our economy is simply insane. Any young biology student could tell you it’s an impossibility to keep depleting resources from an ecosystem and expect it to survive. And yet, every year, governments worldwide — even when we are in the grip of a global pandemic — resolutely keep their focus on increasing the only measurement of growth that is valued — gross domestic product, GDP.

How did we get here?

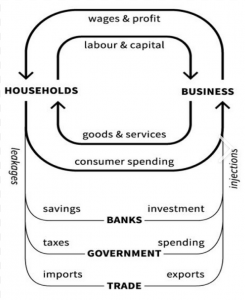

Our modern economic system grew from the iconic diagram of the circular flow of income drawn by Paul Samuelson. Even I can draw that one. Households supply their labour and capital in return for wages and profits. Households then spend that income buying foods and services.

Voila — the interdependence of production and consumption that is the marvellous market. There are three other loops. They are banks, governments and trade. Banks take some of the income and use it as savings which they invest, and return some of the money as interest (but not all). Governments extract taxes from income but put it back into the system as public spending (but often not enough). International trade balances imports with exports (but not always, hence trade deficits).

But it was arch-neoliberalists Friedman and Hayek who constructed the narrative that has underpinned laissex-faire economics as we know it today. It is a school of thought that allows for minimal interference by government in the economic issues of individuals or society. It is free market capitalism that favours reduced government spending, deregulation, globalisation, free trade, and privatisation. It is focused on the production of goods and services for profit which necessitates extraction from both natural and social capital for the benefit of a minority and without taking into account the systemic impact — either on ecological or social capital. {If you want to dive deeper into this history I recommend Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth.}

There are a number of other factors and a set of rules that we need to consider, both of which underpin the economic system of laissez faire capitalism; how capital works and in particular, debt, and the structure of ownership of organisations and properties.

Firstly, the rules. Donella Meadows, one of the greatest systems thinkers of our time, made clear that the rules of the system are one of the most valuable places to intervene to create change. The rules of the economic system grew from the dominant mindset of the day (see Part 4for more on how we think influences how we design the world). The rules of the extractive economy are individualistic, they advocate that the individual is the most important unit of consideration. The underlying theme that sits on top of that, like a layer cake, is maximising profits and minimising risk. When the rule of the individual supremacy is coupled with the notion of maximising profits and minimising risk, what you get is a financial system that extracts wealth for itself but doesn’t consider the human or ecological cost to other individuals. The rules apply whether you are homeowner on whose mortgage a bank forecloses, a global fossil fuel business whose purpose is to provide energy that fuels economic growth but destroys the biosphere, or a manager who brutalises his team for sales performance outcomes in order to get a promotion.

Ownership is the engine of our extractive economy. Capital and debt are its servants. No-one knows more about this than Marjorie Kelly. In her seminal book Owning Our Future she states:

“Ownership is the gravitational force that holds our economy in its orbit, locking us all into behaviours that lead to financial excess and ecological overshoot. It is ownership that makes wealth creation possible.”

The primary model of ownership in business is the limited liability company. The entire construct is legally underpinned by idea that the individuals that own or run a company have little liability for the impact that organisation has on people or planet. The adult that grew from the limited liability child, is the publicly traded global corporation. These now represent approximately 80% of global economic output.

Publicly traded corporations trade not only in commodities and services, but in shares which are traded on stock markets all around the globe. When a company is made public and shares are issued, these shares are ascribed a value based on the turnover and profit of the organisation. They increase in value dependent on its projected growth, and the growth of its profits. The only reason anyone has to buy shares is to make a profit when they are sold. The only way in which they make a profit is if the company that publishes the shares continues to grow and generate more profit which is shared with the shareholders. And so the scene is set for indiscriminate, unfettered, growth to occur. The impact of unfettered growth is somewhat held in check by the regulatory environment, but not much.

Questions about who owns and controls the methods of production of wealth, and who benefits from that wealth is one of the fundamental questions a regenrative economy has to answer.

A supporting player in this particular drama is the ownership of the commons. The commons are the life support systems of planet earth. Air, land, soil, forests, rivers, oceans, rocks, minerals, ore and the life they contain. From microorganisms to fish, and increasingly the industrial production of animals and grain for human food. In Europe, the enclosure of the commons goes back many generations before the industrial and corporate revolution began. It was, if you like, the practice ground for power-grabbing, perpetrated on its own people by royalty and robber barons. If you own the land, you own the power to extract from it and the power to extract from it builds your personal power and wealth. The European colonialism project followed up on the enclosure of the commons and extended the practice to a worldwide enterprise. Global commodity corporations to supply grains for food, ore for industry, people for labour (slavery) established in the colonial period have over time, mutated into the global corporate landscape we know today.

Questions about who really owns and controls air, soil, water, forests, oceans, animals, ore and minerals is the second fundamental question a regenerative economy has to answer.

Finally there is capital and debt. What western economies (capitalism) do is turn the invisible into visible assets that can be monetised. So everything that exists, that moves and creeps and crawls, can be turned into an asset – from l and, to forests, to houses, to equipment, to farm animals – and is documented in some form of ownership. Assets can have a value ascribed to them, that value can transformed into capital, that capital can be loaned to others through a banking system, and it can also allow you to borrow more yourself as the system can hold a record of your ability to pay back what you are loaned. The more assets you have, the wealthier you are, the more wealth you can accrue. This is a reinforcing feedback loop, or what we describe as the law of more begets more.

On the surface this sounds attractive, and it is. It has driven an enormous lift in human conditions in the last 200 years. Yet just as with Samuelson’s economic model, the energy and natural resources on which this economy and consumption depend are missing from the financial model. So too are the people who live in societies that the financial systems affects — whether that effect is on their mental or physical health.

There are also other dark sides to this equation which are called debt traps. They are to do with the power that loan agents of whatever kind — from a bank to a loan shark — has over the asset. Most loans are secured loans, unsecured loans are much harder to come by. They are secured on the assets you have in your possession which can always be sold to someone else. When the prime asset can be sold to someone else, any moral obligation the loan agent has to care for the recipient of the loan, disappears. The financial system therefore encourages debt because it makes more money from debt. When you cannot repay, loans can be rolled over usually at much higher levels of interest. Until the time comes when you can no longer manage the debt trap in which you find yourself, and the sharks move in and take your primary asset. Whether that is asset stripping a company, or taking your home from underneath your feet. Almost every contract you enter into — from a mortgage to your internet host provider — can be sold to someone else, often without your knowledge.

This process is reflected in the global financial system. It is normal for richer countries to offer loans to poorer countries. In the case of China and Africa for example, which is following and even ‘improving’ on the ‘extractive rules’ laid out in the time of European colonialism, China is now the single largest creditor to Africa, accounting for almost 20 percent of all debts owed by the continent. Countries with the largest Chinese debt include Angola at US$25 billion, Ethiopia at US$13.5 billion, Zambia at US$7.4 billion, Congo at US$7.3 billion, and Sudan at US$6.4 billion. Loans are given to develop mining industries; the extracted ore is shipped back to China where goods are produced to be sold in African markets, usually at a much cheaper price than can be produced locally because of China’s access to its own cheap labour. It also provides loans for massive infrastructure projects which contain a clause that if the nation defaults, the asset is retained by the loan nation, China or implement policies that are beneficial to China. The port of Mombasa in Kenya is collateral for the investment in the $2.3billion SGR railway project.

These are some of the processes of financial extraction. What has been accelerating in the past 2–3 decades, has been the process of wealth extraction to a very small percent of the global population. It accelerated again in the last 12 years when the fiscal elite got the shock of a lifetime in the 2008 financial crash. The deep misconception in this process — just as with ecological limits — is that financial extraction from the masses in favour of the elite few, can continue forever. That there is no limit to it. But the constraint the system puts on it, is the ability to pay back.

In no other financial event of my lifetime was this better illustrated than 2008, where the prime lending market fell over and thousands upon thousands of people — particularly in the US — could no longer pay back their property loans. The cascading implosion and contraction of global economies heralded a decade of austerity, and the cobbled together solution gave the financial elite a bandaid which has allowed another 10 years of extraction to compound the original situation.

In times of crisis, leadership can go in different directions — into fear, scarcity, and survival or into the recognition that something new has to be born from the ashes of the old. A golden opportunity to really kickstart transformative change post 2008 was missed and put of until the next global crisis arrived. Covid19.

The emergence of the butterfly?

The idea that constant growth is possible on a finite planet under the multiple existential threats of climate change, biodiversity collapse, food system fracturing, deforestation, ocean acidification — all of which are driven by the consumption that is required for the economic model of constant growth — has now been under question by leading economic thinkers like Mariana Mazzucato and Kate Raworth for some years. Before them there was Donella Meadows, who, when she published the seminal work Limits To Growth in 1972, foresaw the environmental and economic collapse that was to come.

This is the role of the regenerative economist and practitioner. To find ways in which to grow the new, to imagine the unimagined, to design a new container in which economics works differently. The complexity which accompanies the global economy, the interconnectedness of systems it has created, is not easily unpicked, especially since it is bolstered by powerful vested interests. We have been building a global economy so long, it’s almost hard to remember economies that were not tied to the relentlessly extractive process of more.

Yet there are many theories and models emerging that offer light at the end of this dark tunnel. They offer ways in which we might change our global economy to halt the extractive and divisive economies which offer opportunities of exponential wealth and power to so few, and leave the rest of the world struggling to get by. Many of the most hopeful are focused on changing our places. They range from upgrading the failed idea of sustainability to a circular economy; to smart cities with better relationships to their rural surroundings; to doughnut economics, to human-centred incremental improvements and the wellbeing economy.

And then there is regenerative economy design.

In nature there is a process, beautifully described by ecologist Elisabet Sahtouris in the story of the butterfly. The caterpillar and the butterfly which emerges from the caterpillar’s chrisalis has no single strand of DNA in common. As the caterpillar cocoons, tiny imaginal cells activate deep inside its structure which allow the total transformation of matter to form the DNA of a species that is utterly different from the first. In chemistry it’s called a phase shift — the transformation of matter from one state to another — from water to solid water to ice. A regenerative economy is unlikely to be just an improvement on the existing economy or even a transition to a sustainable economy. It will be a reinvented economy.

A definition of regenerative economics

According to many different dictionary definitions regeneration is an act or the process of regenerating : the state of ‘something’ being regenerated. It is also described as a spiritual renewal or revival; and the renewal or restoration of a body, bodily part, or biological system (such as a forest) after injury or as a normal process.

If we look at its ancient Greek roots — as both Carol Sanford and Kate Raworth have reminded us — economics was a term first coined by Aristotle who ‘defined it as the pragmatic science of living virtuously as a member of the polis (or community) through wise household management.’

Thus regenerative economics is the restoration of intelligent and wise management of our global planetary ecosystem whilst reigniting a spiritual renewal or developmental growth stage of the human species.

This is what a regenerative economy seeks to adjust and change. It fundamentally seeks to create an economy in which the planetary ecosystem and its resources are respected, not depleted beyond the ability to sustain planetary health, and in which the huma experience is one which allows all humans to achieve their highest potential through constant development and growth. A regenerative economy would recognise the right to life not just of humans but all species — in a state of constant evolution.

This series deals with economic change that is sourced from place, a foundational pillar in designing regenerative economies. It deals with the varying aspects of bringing our economies back towards a localised, place-sourced design that derives its vitality from the interconnected thrivability of the five key capitals that surround it – ecological, social, human, production, financial — whilst still operating inside our existing global economy as it slowly transforms. It’s a g-local approach. It is an economy that is rooted in the natural geology, geography topigraphy of place, alongside the unique cultural heritage that each and every region on this earth can draw upon.

Wisdom is built on solid foundation of knowledge and discernment – in context.Before we arrive at the process of design for a regenerative economy, there are a number of additional fields of knowledge that we need to hold us up as we do, and questions we should explore.

- Are we designing a regenerative economy for transformation of the existing system or its collapse?

- How might living systems (complex adaptive systems) work as a base model for regenerative economics?

- How can systems thinking be applied for regenerative change?

- How the way in which we think affects the way in which we design

The next four parts of this paper deal with these subjects.

The Economy of Place is a series of articles by Jenny Andersson that are edited parts of her unpublished book Renewal. There are 20 parts to this paper which will be published here in due course. If you would like early notification of future releases, please register at Really Regenerative — Economy of Place.

Many people have helped me shape these narratives. I stand always on the shoulders of giants in regenerative economics and business like Carol Sanford and Kate Raworth, regenerative leaders who understand place such as Pamela Mang, Ben Haggard, Daniel Christian Wahl, but also many anthropologists, ecologists like Joanna Macy, developmental psychologists, bioregionalists, regenerative finance specialists and many others. I know so much less than they. If I ever publish the whole book I will reference you all but my gratitude is not less because I can’t mention you all here.

Recent Comments